This morning as I was making my rounds on social media before my day began, I came across a tweet from a good friend, and even better meteorologist, Ryan Vaughan. Apparently overnight some hail producing thunderstorms had rolled through his area after his forecast mentioned that the trough responsible for the thunderstorms would remain south of the area. Unfortunately, his forecast was off by about 100 miles, which is really good when you consider he’s attempting to forecast something that is “invisible”. But as someone who takes pride in his work, he was a tad disappointed. Ryan’s tweet simply stated,

“God sure has sent me a couple of slices of humble pie lately when it comes to forecasting. As I’ve said, sometimes we forecast, he laughs.”

After seeing this tweet, and thinking about how humbling forecasting can be, I came across a thread on a message board that was discussing the recently released AccuWeather Seasonal Tornado Forecast. In the thread it was brought up just how bad AccuWeather’s 2011 – 2012 Seasonal Winter Weather forecast had been (image below).

This forecast was particularly atrocious when you consider the November 2011 – January 2012 average temperature and precipitation maps shown below. As you can see, the area on the AccuWeather forecast that was to experience cold and snow conditions has actually observed temperatures that are well above normal and precipitation amounts largely below what is expected. In fact, places such as Midland, TX have received just as much, or more, snow than places across the midwest. Northeast Arkansas had received more snow by November (~10 inches in places) than Chicago, IL and Buffalo, NY had received by mid-January.

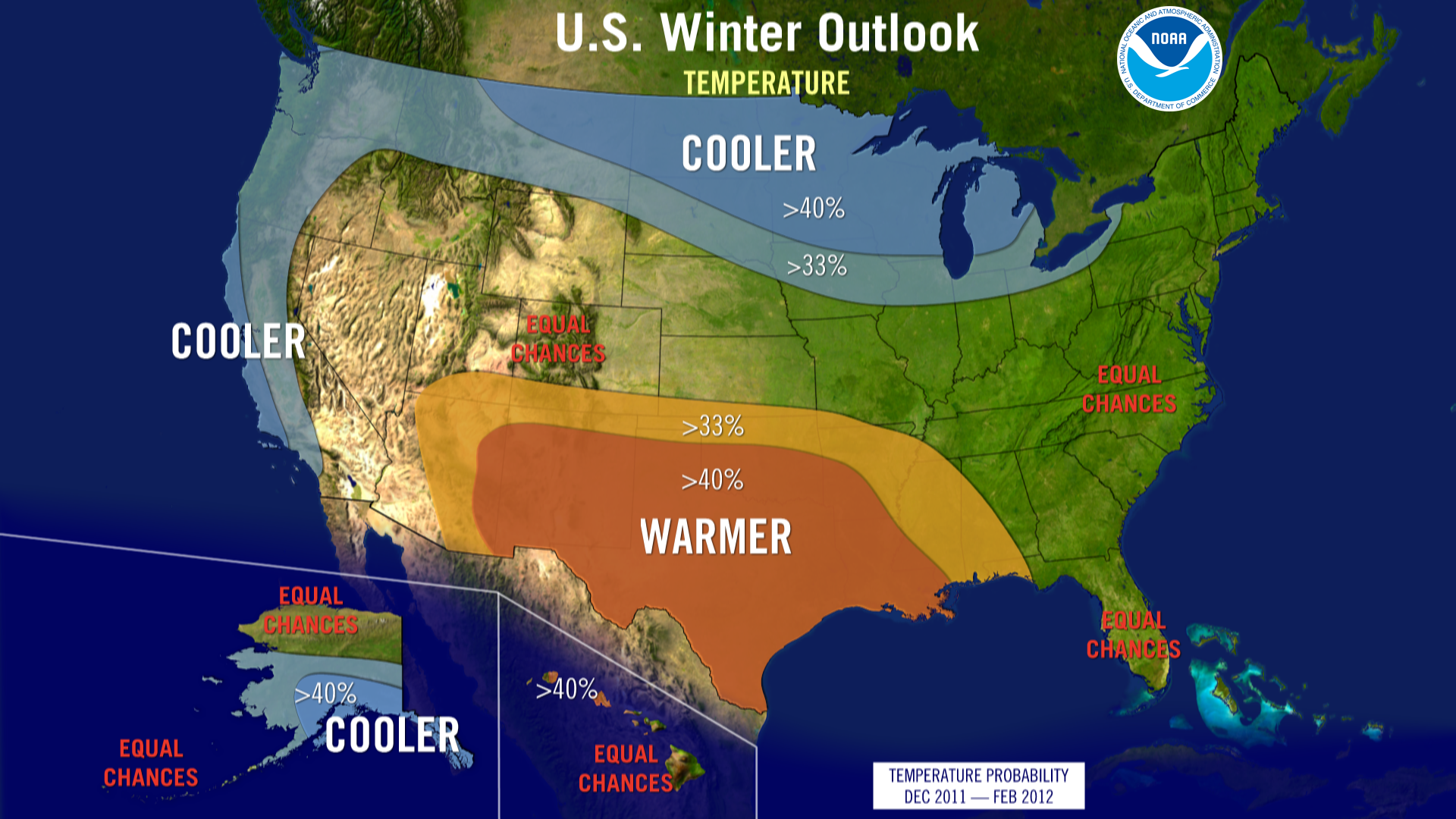

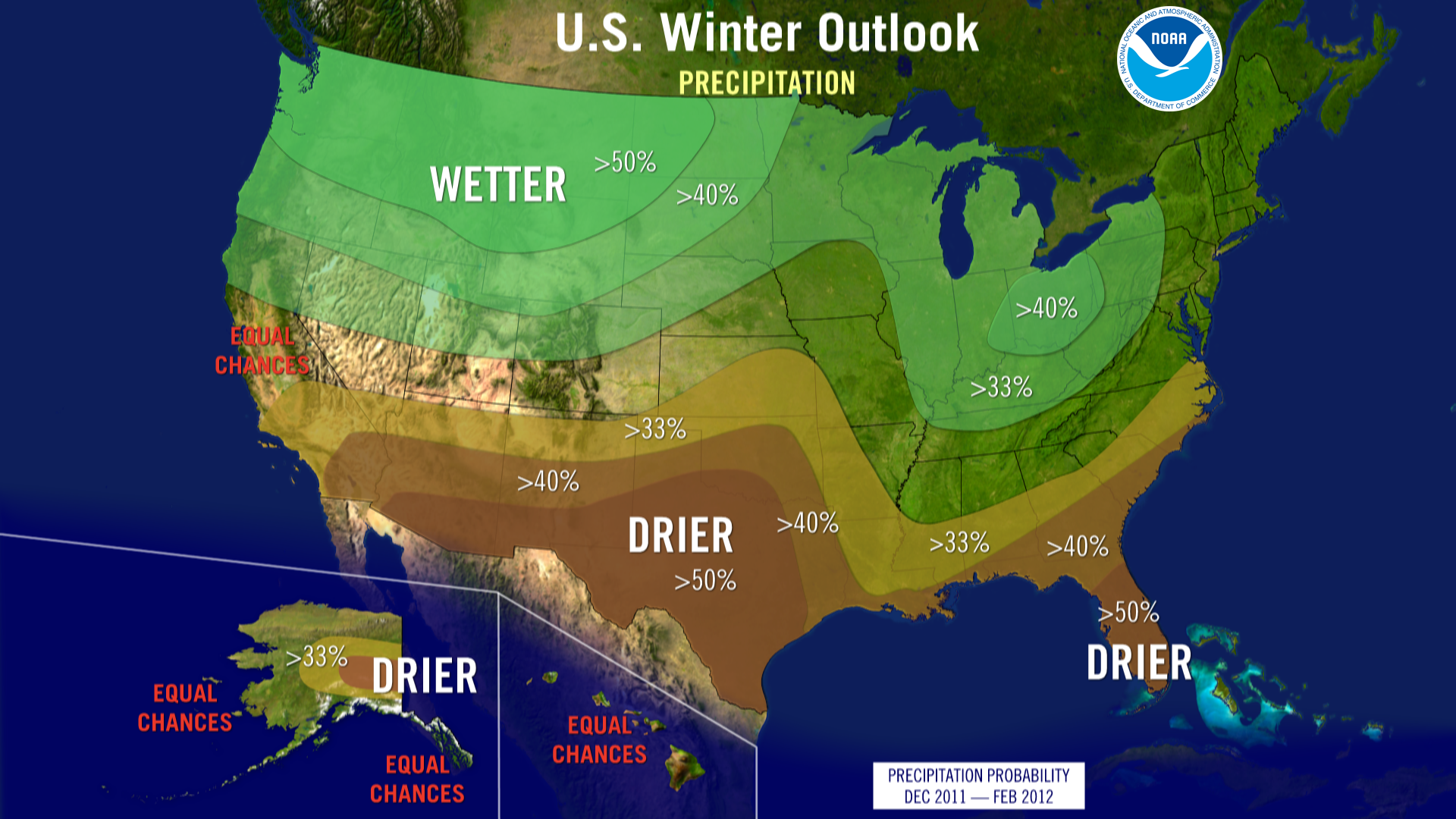

But this discussion isn’t about AccuWeather per se. To prove my point, here are the forecasts from the NOAA/NWS Climate Prediction Center. They are slightly better than AccuWeather on the temperatures across the south, but still call for cooler weather (than normal) across the north. The precipitation forecasts are almost 180 degrees out of phase from what happened in reality.

Don’t get me wrong; seasonal forecasting is hard. There is a reason why the severe convective hazards research community has resisted making seasonal tornado outlooks for so long — there is just too much intra-seasonal variability! But what really bothers me is when people use a forecasting philosophy of persistance on the seasonal scale. The idea behind persistance is that the atmosphere is in a relatively stable state and what’s previously happened will continue to “persist”.

In the southern plains, the first half of February 2011 was a winter nightmare. Two major winter storms traversed the area in the span of two weeks, with a comparatively “minor” winter weather event in between. (Note, that this “minor” winter weather event would have been considered a fairly significant one during a “normal” winter — whatever that is!) In addition to heavy snow, these winter storms were also accompanied by bitter cold. In fact, during this approximately two week span, Oklahoma set it’s all-time record low temperature and Arkansas reported it’s greatest 24-hour snowfall accumulation in history.

What people failed to remember was that this occurred in the midst of an extremely warm and dry winter. As cold as it was in Oklahoma during the first half of February 2011, the second half was even warmer than the first half was cold! Remember the record low set? Less than a week later the temperature had warmed over 100 degrees Fahrenheit at the same location! In fact, Oklahoma finished the month either near “normal” or slightly above normal in terms of average temperature.

During the winter of 2011-2012 2010-2011, Earth was experiencing a La Nina pattern. Namely, the waters of the central Pacific were cooler than normal. This has profound impacts downstream (i.e., over the United States). Typically during a La Nina, the CONUS is drier and milder than average, but due to atmospheric processes I won’t discuss here, is subject to extreme cold outbreaks. If one of these extreme cold outbreaks encounters moisture, then the recipe for a winter storms is well on it’s way to completion — as was the case in early February 2011.

To illustrate just how dry the winter of 2010-2011 2011-2012 was for the southern United States, below are a series of images from the U.S. Drought Monitor. It shows that in October 2010 (before the 2010-2011 winter) that much of the southern plains was experiencing normal to slight drought conditions. Fast forward 4 months and that picture had changed (Second image: February 2011 — after the barrage of winter storms). Pretty much everywhere in the southern plains was experiencing a drought. A drought that would persist through the Summer, culminating in the worst category of drought by October 2011 (Third Image).

When seasonal forecasts called for a repeat performance of La Nina this winter (not that La Nina’s are “repeatable”), a lot of those in the weather business called for a repeat of last winter’s conditions, which to a 0th order is reasonable expectation. So imagine my surprise when people tended to remember and focus on the two week period of extreme cold and heavy snow, rather than the season-long drought and mild conditions. I nearly fell out of my chair when I heard a local television meteorologists talk about how since we had X last winter and we got a lot of cold and snow, and X is expected this winter it should be a cold and snowy winter. How quickly we tend to forget! Out perceptions of what happened is affected more by extreme, unusual, and disrupting events, rather than the long-term mundane average. So, how did the forecast for a cold, snowy winter pan out? Well as you can see above, it’s been wetter and warmer than normal. It’s been so wet in fact, we’ve made substantial progress in overcoming a large part of our drought (below). Although, we still have a long ways to go.

So, what’t the take away point? Seasonal forecasting is hard. At its current optimum, it is slightly better than an educated guess (although, some might argue that all forecasting is this way!). So, when you hear the prognosticators try to spin their poor seasonal forecasts, you should know better than to fall for it. And when they offer you their next “highly accurate” and “highly detailed” seasonal forecasts, you’ll know exactly what to do with it. Take it with a grain of salt.